Step One: Define your study area

The size and shape of your study area will depend on a variety of factors including community capacity (funding, personnel, volunteer support), the landscape (scale, complexity), or if neighboring communities are also participating. You may want to begin with a single corridor, or corridor segment, and then branch out to others in the future. Consider also working with other communities in the region on a major road corridor that encompasses several municipalities. This type of coordinated effort can yield more consistent results across municipal lines.

Step Two: Create a base map

You will need to gather data on the corridor study-area you have selected and compile them into a serviceable map. This base map will form the graphic basis for your study. Have a map printed that includes your target area. Nearly all Vermont communities have access to Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping, which provides access to many different digital “layers” of information. The following information, or “layers,” are useful to include on a base map:

- Orthophotograph (an aerial photograph corrected to be measurable, like a map)

- Property lines, including road rights of way and privately owned parcels

- Road and street names

- Municipal boundaries

- Contour lines (topography)

- Underground utility lines, such as sewer and water

- Current zoning districts

- Prime agricultural soils

- Wetlands

- Historic sites

- Floodplains

- Wildlife habitat

- Endangered plant species

- Public or conserved lands

TIP: This map should help you begin to understand the issues, opportunities and constraints of the corridor. Also, you do not have to have all the “layers” on one map. Multiple maps or a larger sized map can be used – whatever serves your needs.

Step Three: Conduct a visual analysis

A visual analysis simply means using images to understand the visual qualities of an environment. Photographs, maps, and other graphic materials can help you break down complex landscapes into manageable components. This analysis will help your community understand the landscape along the corridor – what it is now, how it evolved and how it may be significant.

Landscape inventory

The purpose of a landscape inventory is to identify the presence and location of physical features and other factors that present development opportunities and constraints. The inventory usually consists of a map containing a range of available data, such as:

- Topography

- Soils

- Transportation infrastructure

- Utilities

- Historic sites

- Floodplains

- Wildlife habitat

- Endangered plant species habitat

- Prime agricultural land

- Public or conserved land

- Land ownership

- Zoning districts

Some of these features present physical constraints to development. Mapping steep terrain, floodplains, and wetlands will help you identify areas where construction is less likely to occur. Barriers such as railroads and slopes can prevent access to suitable lands. Other factors – such as conservation easements, endangered species habitat, or prime agricultural land designation – may present legal or regulatory limits to development. On the other hand, transportation infrastructure, utilities, and buildable soils all present development opportunities.

As you begin to compile the layers of information on the landscape inventory map, you will begin to see which areas of the corridor are best suited for development and which areas will likely remain undeveloped. Also investigate the current pace of growth, recent zoning and building applications and permits to obtain information on development demands and trends.

Tip: Do not just rely on the map – get outside and walk the land to gain a sense of how physical features fit together. Also consider having low elevation aerial photographs taken of the corridor as they can illustrate context more effectively.

Landscape and land use history

Reviewing historic settlement patterns provides useful clues about former land uses and landscape features. Looking at then-and-now photography can show the contrast and the cumulative effects of incremental change. Some useful places to look for historic photographs include:

- Local historical societies

- Archives

- Published works on local history

- Community outreach

- Historical aerial photographs

- Historic records

Scenic inventory

Before you can conduct a scenic assessment, inventory and map the scenic resources along the corridor – in other words, locate the better views. In pairs or small groups, travel the road corridor stopping to photograph every view that has scenic qualities. Record the location of each viewpoint on a map. Take an outbound trip, then repeat the process on an inbound trip. As you ride along, note on the map points of visual interest – places where the landscape changes, edges of settled areas, historic landmarks – anything that seems particularly distinctive or memorable. Record the bad as well as the good and any problem areas; note them on the map.

Scenic assessment

Using the images you gathered during the scenic inventory, assess the value of scenery along the corridor. You have two basic alternatives – you can conduct a formal quantitative process, or opt for a looser, more qualitative approach. Scenic assessment enables you to pinpoint key scenic resources within your corridor. After you have defined and located them, you should determine which of those scenic resource areas are threatened by development or susceptible to change. A site analysis (the next step) will help you to understand and articulate the landscape patterns that contribute to those views.

Quantitative approach

This approach defines a set of criteria, and evaluates views to determine whether they possess certain attributes. These are characteristics widely recognized as creating scenic value, such as contrast, layering, focal point, uniqueness, etc. Images are scored in each category and assigned a numeric score to determine their overall scenic value. For example, a view with clearly discernible landscape elements (such as a wooded edge along a field), a point to which the eye is drawn (a distant mountain), and features that are unique to a region (vernacular architecture) would receive a higher score. You can do this as a group, or consider hiring a consultant to complete this task. The benefit of this approach is that it is more rational and defensible.

Example of Scenic Inventory/Scenic Assessment System: Scenic value can be measured using a system that identifies specific criteria. A matrix was used by the State of Vermont to assess scenic value around its interstate interchanges. Landscape photographs taken along the corridor were scored according to whether they possessed those attributes.This view scored high in the assessment and thus was identified as an important scenic resource. It possesses contrast, order, layering, a focal point, uniqueness, and intactness-all positive attributes listed by State policies as contributing to scenic value.

Qualitative approach

Rather than rely on a prescribed set of scenic characteristics, a group develops its own criteria based on what it particularly likes. There are different methods for determining the group’s preferences, but to be effective the process the process should involve looking at a number of views and discussing them.

Sample Approach: An example of this approach would be a mapping and discussion exercise. After reviewing the site photographs and drawings on personal experience, group members individually locate their favorite views on a single map. Views with the highest value will become apparent as several members mark the spots where the best-loved views are located. After discussing what, specifically, makes those landscapes special or unique, the group makes a list of characteristics it finds compelling.

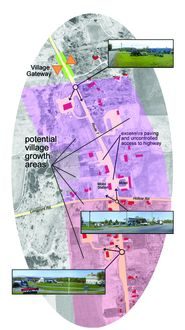

Site analysis

A site analysis is a visual tool consisting of a map or site diagram that conveys landscape information. It marks the location of specific features and illustrates the relationship between those features. Creating a site analysis will help you see existing landscape patterns as well as development and conservation opportunities.

After you have mapped scenic resources along the corridor and determined which are most valuable, analyze the physical and development potential for the land. As you conduct your site analysis, here are some key questions to answer for each high-value parcel in your study area:

- Who owns the land? Does the owner have a plan for it?

- What uses are currently allowed for development in that district?

- Are there any conditions that preclude development (wetlands, steep slopes, etc.)?

- Are there features that recommend conservation (prime agricultural soils, rare species, etc.)?

- Do the existing landscape features offer opportunities to develop without diminishing its scenic value (hedgerows, slopes, wooded areas, etc.)?

Your site analysis will help you determine if a property is susceptible to change and whether that change represents a threat to its scenic value. Some high-value lands may already be conserved or may be unlikely to be altered, while others are ripe for development. You should set priorities, deciding on which parcels to concentrate.

Step 4: Consider Options For Preserving Scenic Resources

Once you have determined which segments of the road need your attention, what should you do to protect their visual integrity? Conservation and regulation are strategies that can be utilized. Protecting and enhancing valued landscapes requires supporting their underlying structure and replicating their patterns. If it follows traditional patterns, new development can enhance rather than detract fro a scenic landscape.

As you learn about the forces and activities that shaped the scenic resources along the road corridor, look for ways to strengthen and preserve them. For example if your most scenic land is farmland, develop a strategy to support the agricultural economy of your region. Sometimes, adding features to an existing landscape can enhance its scenic value. Screening parking lots is one example; planting a double row of shade trees along the road is another. In village areas, inserting new buildings can re-establish a dense fabric as well as providing needed commercial space.