By Jack Hanson

In 2000, the State of Vermont created Efficiency Vermont, a utility focused on reducing waste in the electricity sector, and reducing overall electric power consumption in Vermont. The logic was simple: instead of spending money to build or procure more power sources, Vermont decided to invest money in reducing demand for electricity, thereby saving consumers money and avoiding high-cost investments in power supply and the infrastructure needed to support a larger system.

It worked. Twenty years later, despite the proliferation of power-consuming devices such as smartphones, tablets, and laptops, Vermonters are using less electricity today than we did in 1999. Controlling demand has allowed us to keep costs down and make our electricity sector cleaner. It has also positioned us to accommodate the new load (power demand) of a growing number of electric vehicles and electric heat pumps. Vermont Energy Investment Corporation, which manages Efficiency Vermont, has been so successful that it consults with partners around the world seeking to reap the same benefits.

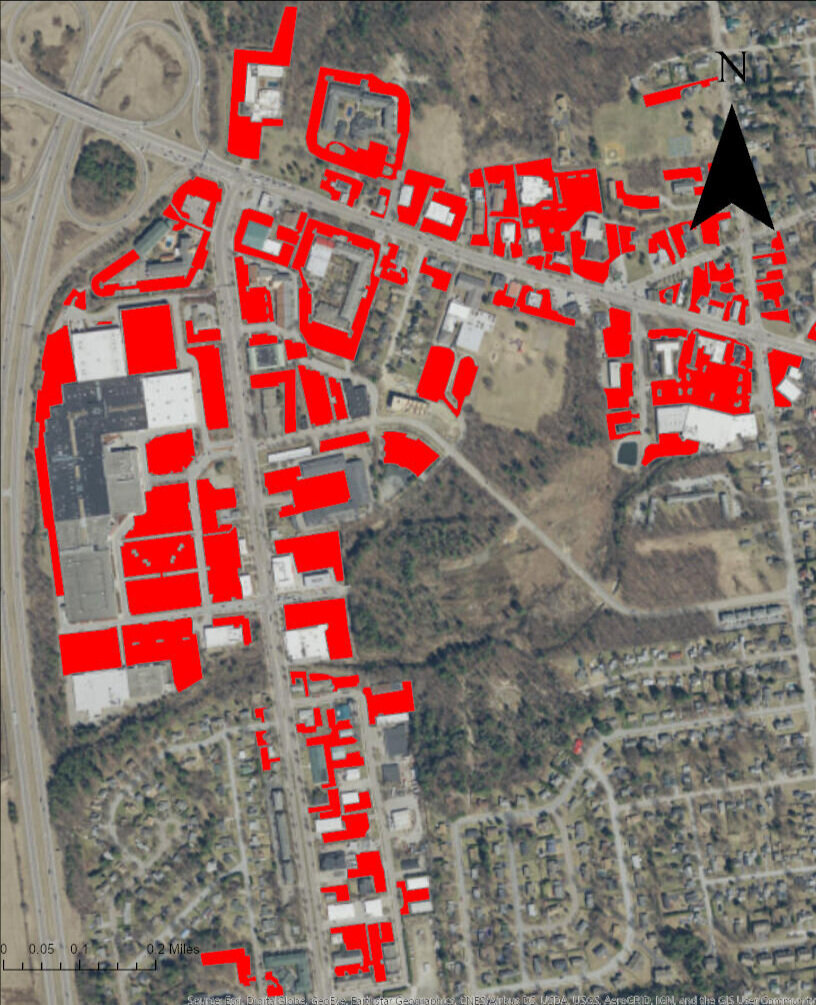

Unfortunately, over the same time period, Vermont policymakers have failed to apply the logic of reducing demand to our transportation sector. Instead, we have expanded supply–building new roads, lanes and parking spaces. We require developers to build excessive amounts of parking, which cost tens of thousands of dollars for each space and perpetuate the myth that it is “free.”

The subsidies and investments we’ve made to increase supply have worked to incentivize and spur greater demand. As a result, Vermont has one of the highest vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per capita of any state in the country, even among rural states. This matters a lot, because transportation is the top driver of climate change in the U.S. In Vermont, it represents almost half of our total emissions. It is also Vermonters’ second highest expense after housing.

Just as reducing the demand for electricity helped us avoid building expensive power plants, investing in measures that reduce the number of people driving vehicles alone, will help us avoid spending money on expensive highway infrastructure.

This model is called Transportation Demand Management, (TDM) and there are plenty of examples of it working in Vermont and elsewhere. At the University of Vermont, there is a demand for parking spaces, but not enough land or money available to build them. So UVM has employed TDM measures such as offering free bus passes, and incentives for carpooling and walking, along with on-campus parking fees to lower the demand for spaces. Prior to undertaking these efforts, UVM employee’s commuting habits were similar to others in Chittenden County–around 75% in a single occupancy vehicle (SOV). Today that number is 55%.

While 55% is an improvement, UVM and others can do much better. At the Center for Research on Vermont, a small team of us have done targeted outreach to UVM employees who hold a parking permit. We’ve made them aware of the incentive programs available to support non-SOV commuting, and offered additional one-time incentives for them to give sustainable modes of transportation a shot. It has been quite successful. Thirty UVM employees have traded in their permits for 6 months and are commuting sustainably at least 4 days per week.

We are now expanding this one-time incentive program to all workers in Chittenden County. If you, or any of your coworkers or employees, currently drive alone to work every day, consider reaching out to STVT for incentives and support to switch to more sustainable and cost-effective travel options.

Of course, there are some people whose schedules are so variable and so unique that the only way for them to meet their families’ needs is to drive alone to work every day. But most Chittenden County commuters have the option to use the bus, to carpool, or to bicycle or e-bicycle to work at least a few days a week. And the beauty of it is this: like efficiency measures, the benefits of sustainable commuting are not just to participants; they extend to non-participants as well. Each SOV car trip that we eliminate through these efforts improves air quality and reduces carbon pollution for all. It makes the streets safer for all. It reduces the amount of public money needed for road repair, reducing taxes for all. It eases congestion, especially for others commuting to that same workplace. And it frees up parking spaces for those who need them.

Large and small cities throughout the country are influencing how people move around by implementing TDM measures. The Vermont House Transportation Committee is considering a pilot program to inspire employers, particularly those with over 500 employees, to give TDM a try. The City of Burlington is considering TDM requirements for new, large developments.

Unlike other regulatory requirements, this is one that will save money for businesses, their employees, and their customers. As with the parking permit trade-in, sometimes all it takes is a little push to get someone to make a change that benefits their quality of life and pocketbook. In this case, the employers themselves are the ones getting the nudge. The State of Vermont itself is an employer of over 500. They must lead by example.

Which brings us back to Efficiency Vermont. The Vermont Energy Investment Corporation (VEIC) has slightly fewer than 500 employees. While they are not eligible for the State’s pilot, there is nothing stopping them from taking action. If the organization has learned anything from its 20 years in efficiency, it will implement TDM sooner rather than later.

VEIC is currently moving to Winooski to reduce overhead costs. While their new building is being constructed, they have a decision to make: how many parking spaces will they build at their new site? Remember, each space will cost the organization tens of thousands of dollars. For that much money, how many employees could they get to commute sustainably? This approach would eliminate the need for parking spaces, reduce their carbon output, and save money for all ratepayers.

VEIC’s mission is to reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions in the most cost-effective manner — for the state of Vermont and among their own staff. Will it honor its values as it makes its own transportation investments?

Jack Hanson graduated from the University of Vermont in 2016 with a degree in Environmental Studies. While finishing his degree, he worked full time on Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign. Since then he has worked in communications, political advocacy and campaign roles. He currently serves on the Burlington City Council, representing Burlington’s East District. This post originally appeared here.