By Stephanie Gomory

I don’t miss much about living in New York City, my home before I moved to Vermont in 2016. Hardest to give up (other than certain foods) was the ease of getting around without a car. The subway, buses, and commuter rails served my daily needs. For more spontaneous travel, I could hail or call a taxi for door-to-door service.

In major metropolitan areas, on-demand transportation is all but taken for granted. Even in places where public transport is limited, companies like Uber, Lyft, and other app-based services power ride-sharing at the push of a button. Not so in Vermont, where these services are either nonexistent or highly limited.

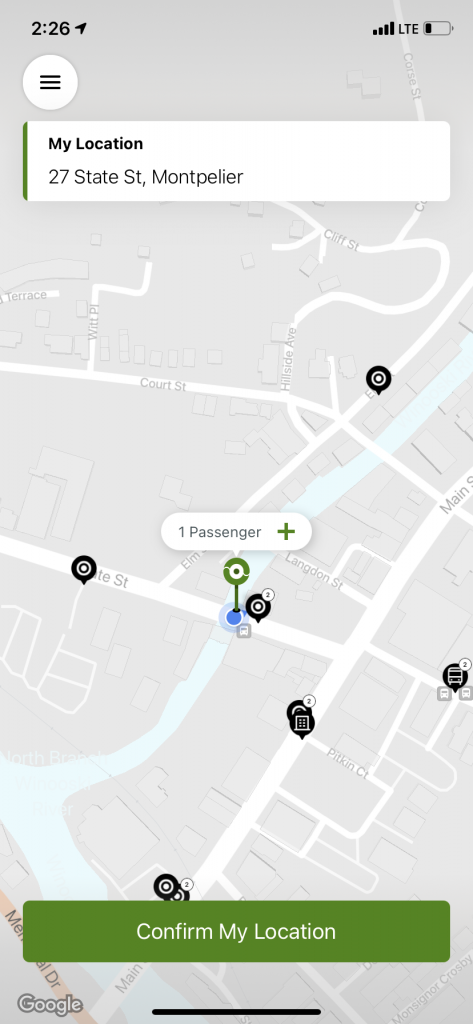

But now, thanks to an innovative microtransit system, Montpelier can enjoy the perks of on-demand transit. MyRide, operated by Green Mountain Transit (GMT), is a two-year pilot project providing flexible-schedule, flexible-route service. It replaced Montpelier’s three fixed-route bus routes in January 2021. MyRide’s service area includes most of Montpelier as well as various destinations in Berlin, including Central Vermont Medical Center (CVMC) and the Berlin Mall.

Passengers can schedule curb-to-curb service by using the MyRide by GMT app or calling the GMT call center; learn more here. Rides arrive within approximately 15 minutes of being requested (if not much sooner; I’ve been on my way in less than 5). You can also pre-schedule rides, including recurring ones for daily trips to work or school.

Due to state policy provisions during COVID-19 (learn more about the 2021 Transportation Bill that VNRC supported), all Vermont public transport, including GMT’s MyRide, are free of charge through June 2022.

Less parking, more housing

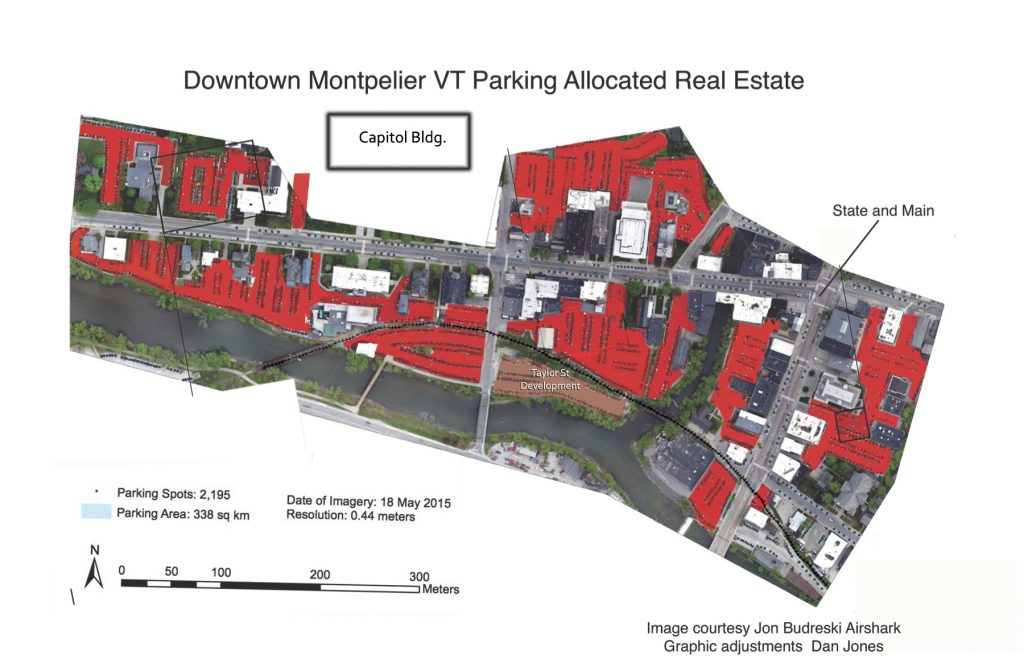

The Sustainable Montpelier Coalition (SMC), GMT’s primary community partner for MyRide, began conceiving of the service in 2018 as a way to alleviate the need for parking in downtown Montpelier. Parking spots currently eat up 60% of the city’s downtown real estate, preventing the development of commercial, residential, and open space that serves the public good.

Elizabeth Parker, Community Engagement Director at SMC, explained that the land use ramifications of ride-sharing are immense. “When people share vehicles, they’re not only reducing their emissions. They’re opening up space downtown for more housing, which in turn saves energy, since more people can live closer to work and amenities, without needing to drive as much,” she said.

This is especially important as our state’s demographics shift. Many older Vermonters are finding it difficult to age in place in rural areas far from services, and are choosing to downsize closer to town. Millennials and young families tend to want to reside downtown as well. In order to nurture these populations—and in the case of younger people, attract them to Vermont—we need places for them to live.

SMC determined that a shared transportation solution in Montpelier geared at reducing parking by approximately 1,000 vehicles could open up four acres for new, mixed-use development. Why 1,000? During (pre-pandemic) workdays, Montpelier’s population swells to nearly 15,000. But in addition to commuters from out of town, SMC found that approximately 1,000 people who live within city limits also drive to work, using public parking spots.

MyRide was ultimately designed to serve this target market: Montpelier residents who drive to town daily but might be persuaded to leave their cars at home if given a viable alternative. Of course, MyRide also serves individuals who were already relying on GMT’s fixed-route bus service in Montpelier, and SMC did extensive outreach to this demographic to ensure they were aware of the upcoming changes.

1,000 Montpelier drivers

I found the 1,000 figure compelling, because I am in this target market. Before COVID-19, I walked most days from my home in Montpelier to VNRC’s office near the State House. But I’d often drive to work or town as well: perhaps it was raining, I was in a hurry, or I needed to pick up items that would be too heavy to carry back home on foot. During my first pregnancy, through parts of an especially icy 2018 winter, walking to and from work just wasn’t a safe option, especially after dark.

But did that mean I wanted to drive? No, not at all. I would have welcomed a service like MyRide then, and I’m enjoying it now. It provides a ride to town without needing to abide by a bus schedule, find or pay for parking, gas up my car, or clean it off in the winter. It also allows the flexibility of traveling to town one way on foot, and then getting a ride back home (say, with groceries in tow—or simply because I’m tired).

In my one-car household, MyRide has allowed another type of flexibility: My spouse and I have been able to go to different destinations at the same time, one of us taking our car, and the other riding with GMT. Previously, we would have avoided scheduling appointments at the same time if it meant we’d be bound by fixed-route, infrequent bus service.

Parker explained that another chief function of microtransit systems like MyRide is “last mile service”: connecting people from their homes to where they pick up public transportation, making public transit both more accessible and more fruitful from an emissions reduction and land use perspective. Someone might take the bus daily to commute from Montpelier to Burlington and back, for instance, but they’d need to drive that “last mile” to and from the bus stop and use up a parking space throughout the day. MyRide can fill that gap.

Public transit is for everyone

The land use motivations for MyRide—reducing the need for downtown parking, freeing up space for people and placemaking—come as counterintuitive to many. I ascribe this to the way that public transportation is implicitly understood in Vermont, and in the broader American culture, as having one purpose only: transporting people who cannot afford or access a vehicle of their own. The thinking goes: Why else take the bus, or any shared ride, if you can at all avoid it?

When I took my first MyRide, on a frosty January afternoon shortly after it launched, my driver echoed this sentiment when I asked how she felt about the new service. She said she thought it would be really useful for individuals who were lower-income, disabled, or elderly—and for children or teenagers who needed a ride to school. In other words, people who could not or did not have a car of their own.

But what about me, a millennial-aged, able-bodied person who owns a car? While I might not have the need for a ride to town, I certainly have the desire for one. I want to reduce emissions, fill up my car with gas less often, and avoid finding parking and paying for it. I also want to live more spontaneously, the way that larger cities afford.

“People who have come from an urban experience enjoy the autonomy of getting around without a vehicle, without having to find parking,” said Parker. I can certainly relate to that, and the data shows I’m not alone. According to a 2018 survey, more than half of adults between the ages of 22 and 37 said a car is not worth the money spent on maintenance, and that they would rather be doing something other than driving. Millennials are used to using ride-sharing and public transit, and are more likely to want shared car access than ownership.

Solutions like MyRide provide options for all members of the community: those who don’t have cars, and those who want to reduce (or eliminate) their reliance on them. “One of our goals is for Montpelier households that have two cars to be able to go down to one car, so that when they want to take a trip out of town, they can; but for simple errands and daily commutes they can use MyRide,” Parker added.

Transportation is the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in Vermont, and Vermonters drive more than the national average. Unless public transit like ride-sharing is seen as a choice for everyone, not just those lacking other options, it will never reach the critical support needed to improve our transportation future and the livability of our communities.

Stephanie Gomory is VNRC’s Communications Director. She lives in Montpelier.