By Jack Hanson, Executive Director of Run on Climate, and Burlington City Councilor

Jack Hanson is the Executive Director of Run on Climate and represents Burlington’s East District on the City Council. From 2019-2021 he worked at Sustainable Transportation Vermont, a research, education, and advocacy organization devoted to reducing car dependency and promoting walking, biking, public transit, and other sustainable modes of travel in Vermont.

When you’re used to driving your own car to work every morning and evening, switching to another mode of transportation might seem daunting, inconvenient, or even impossible. Last year, myself and Phoebe Melchiskey at Sustainable Transportation Vermont partnered with VNRC to explore if a small financial incentive and a small amount of accountability could get Vermonters to do just that – and it worked!

To address the climate crisis we need to address transportation, the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. And to address transportation, we all need to change the way we get around. Especially in Vermont, where we drive far more than the global average – and far more than what our climate can sustain.

The good news is, we can do it – and we’re already on the path. But we need to move much, much faster (which, ironically, involves moving a little bit slower).

Technological advancements are helping. Electric vehicles are becoming cheaper, longer range, and easier to charge quickly in more locations. Electric bicycles – which provide a far greater reduction in emissions than EVs – are also taking off, becoming a great option for trips that many are unable or unwilling to take by normal bicycle.

Policy can and must help. With policy (local, state, and federal) we can incentivize the adoption of new technologies. Policy can also boost the tried and true methods of sustainable transportation: walking, biking, and public transit.

Doing that has a lot to do with changing our infrastructure – for example, passing policies that enable more affordable housing in walkable areas and building safe bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure.

Funding more comprehensive and convenient public transit and building less parking will also help. Policy can accelerate all of these changes.

But at the end of the day, what we need to happen – what all this policy is aimed at – is getting people to stop driving personal automobiles powered by fossil fuels. And when I say “the end of the day”, I really mean it — this has to happen very, very quickly.

With better options made available through better policy and technology, some people will make (or already have made) different choices.

But many others will not — even if they know a safer, cheaper, more convenient option exists. Habits and social norms are powerful.

This is why we need – in addition to policy, infrastructure, and technology – direct behavior interventions. Behavior intervention can serve as a low-cost, simple, effective way to get more people to change their transportation habits permanently, influence those around them to do the same, and create additional demand for alternatives to the single occupancy vehicle.

Last year, working with Sustainable Transportation Vermont in partnership with VNRC, I won a $25,000 grant from the State of Vermont’s Mobility and Transportation Innovation (MTI) program. The MTI program supports “innovative strategies and projects that improve both mobility and access to services for transit-dependent Vermonters, reduce the use of single occupancy vehicles, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions”. My bet was that with this money, I could get 100 people to stop commuting primarily by single occupancy vehicle for six months.

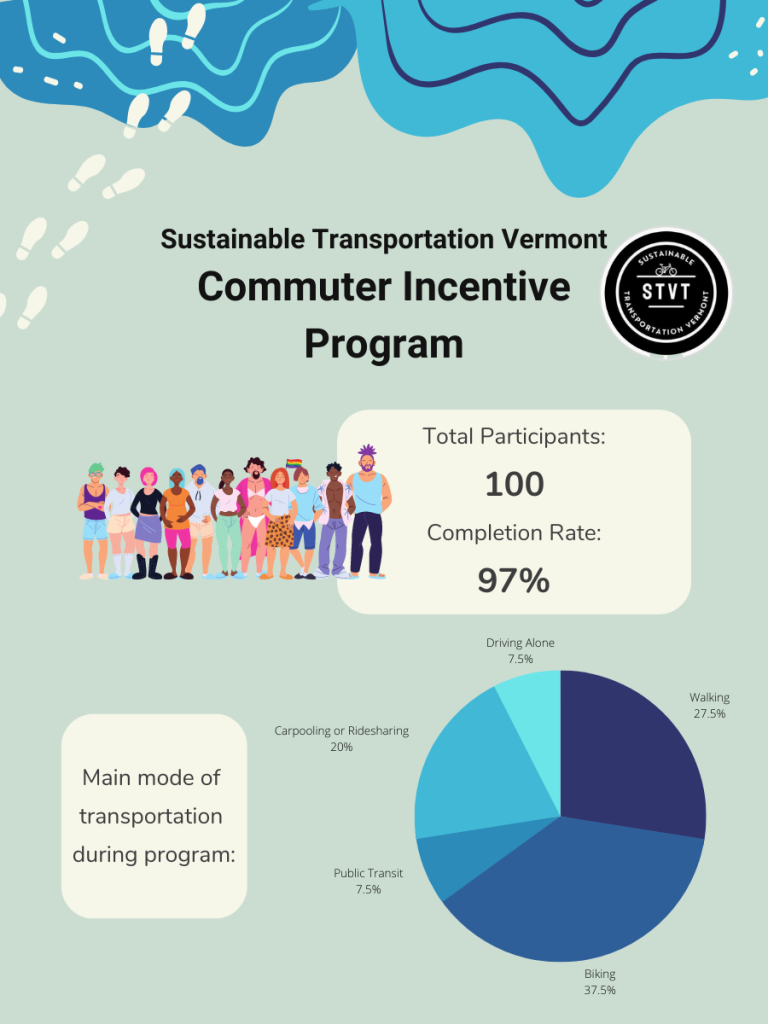

Through simple marketing, gift card incentives, and some basic accountability measures, a year later we had pulled it off – with 98 of the 100 participants fully completing their six month behavior change.

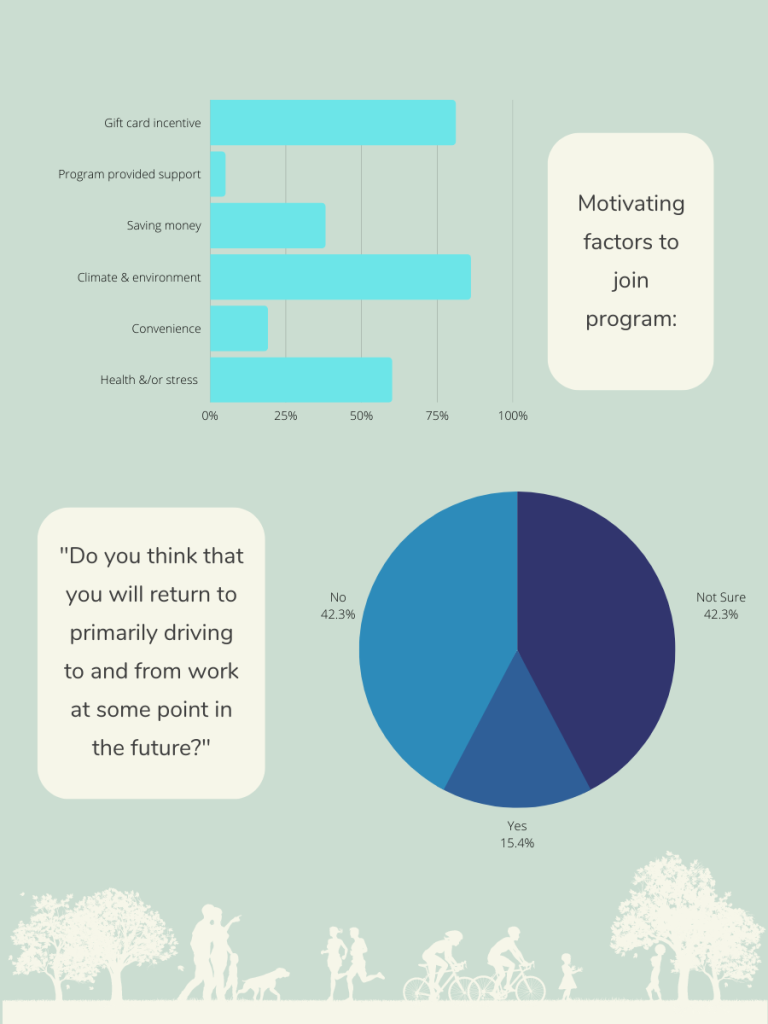

The most exciting part? When interviewed at the end of the program, over 75% of the participants said they planned to continue their new sustainable commuting behavior indefinitely. Only 15.4% of participants said that they planned to revert back to driving alone as their primary way of getting to work at any point in the future.

In other words, for the majority of our participants, we achieved what is likely to be a permanent change to how they commute. Each of those people not only cut their emissions dramatically and saved money, they also became a positive influence on all those around them, including the policymakers that represent them.

Now, you might say “this is all well and good, but it cost $250 per person — we could never afford to scale this up to the level needed to truly shift our society away from single occupancy vehicles.” First, $75 of the $250 was a gift card that the participant then used at a local business, stimulating and supporting our local economy. Secondly, the program could easily become more cost effective if replicated and scaled.

Finally, and most importantly, consider this: between federal, state, and utility incentives, we are giving over $10,000 to Vermonters who purchase a new EV. That means for the cost of getting just three people to switch from an internal combustion vehicle to an electric vehicle, we can get well over 100 people to switch to primarily relying on transportation options that are even more sustainable, cheaper, and safer than EVs.

Of course, not every Vermonter is in the position to change how they commute. But many, probably tens of thousands, are. They just need a small push and a small prize to make the switch. We can easily afford to do that, and by doing so we all benefit by having cleaner air, safer and less congested roadways, and a more stable climate.

Given the enormous economic and human costs of our current transportation system, and knowing that such a simple and cost-effective method exists to help shift it, I would argue that we can’t afford *not* to implement this behavior intervention at scale. If you don’t believe me, I ask you this: would a $75 gift card change your mind?

Image and graphics by Kati Gallagher