By Mary Catherine Graziano

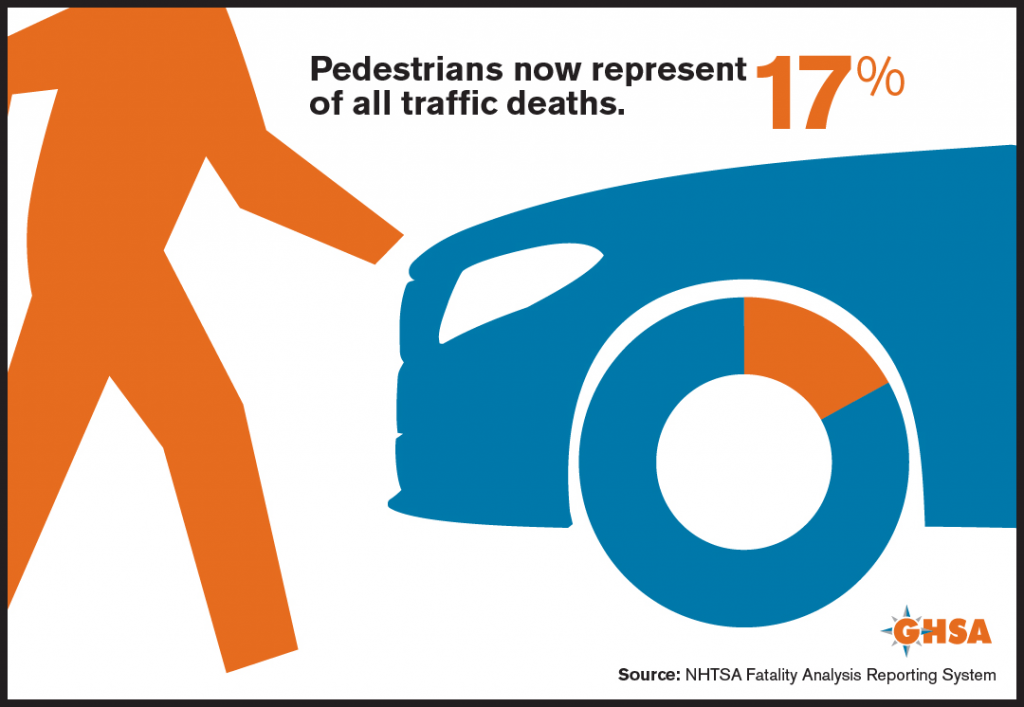

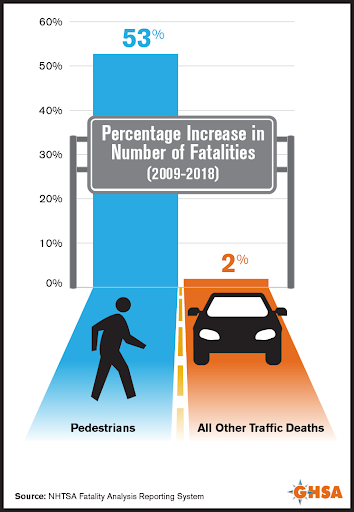

People walking and biking make up nearly 20% of traffic fatalities (pedestrians ~17% and bicyclists ~1.5%) in the United States, even though they make up only 12% of all trips taken. Every year, the fatality and crash rates for people walking and biking have increased. The reasons behind this increase are a complex relationship between increases in average vehicle height and weight, faster speeds on roadways, lack of dedicated walk/bike infrastructure, poverty and wealth, and road design.

One thing is clear, though—fatality and crash rates are not happening because thousands of people suddenly became fatally foolish and began flinging themselves recklessly in front of peoples’ cars.

If you were only judging the crisis based on the way our media talks about crashes, you’d think that our entire nation, collectively, broke scores of mirrors, walked under innumerable ladders, opened umbrellas in entire cities’ worth of houses, and had black cats cross thousands of paths. That’s because we almost always describe a crash as an “accident.” Accidents: also known as peculiar, unpredictable, unsolvable series of events that ended badly. Or, “bad luck.”

But motor vehicle crashes are not freak occurrences; they are entirely predictable events. Crashes happen for numerous reasons, but a primary one is that across the country, our transportation infrastructure is insufficient to keep everyone safe. It might be a poor grading in the road, or poor sight lines for a turn, or a road through a residential area that is broad and straight, encouraging speeding, or a crossing that is too long for an older adult to reach the other side before the light changes. The fact that intersections are the sites of about 26% of crashes between people driving cars and people walking means that even the places meant to be safer for pedestrians are not.

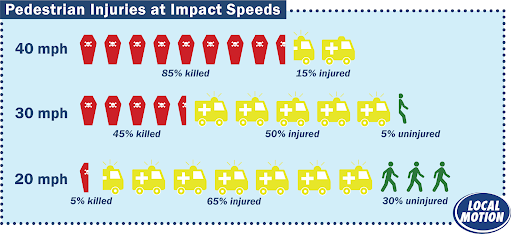

Speed is also a major factor, and is determined by both the design of the road and the posted speed. This matters tremendously, since fatality rates for people walking and biking increase dramatically for every relatively small increase of motor vehicle speed.

We have designed our roads to be most efficient for people driving vehicles, but at the expense of the safety of people who walk or bike or roll on our streets. And we’re all pedestrians at some point in our day: The moment we exit our vehicles to travel to a building, we change from being a motorist to a pedestrian. And those moments that we are pedestrians are incredibly vulnerable ones. Until we get to a “car free” zone, we’re not safe from being struck.

This is not inevitable. The way we design roads in the US may be a habit, but it is also a choice. There are many ways to redesign our roads so that people driving and people walking/biking/rolling can both enjoy a safe, efficient trip. One example: we can narrow the road slightly at an intersection, so that people who are driving are forced to slow down significantly when they get to the intersection, and pedestrians have less road to cross to get to the other side. Slowing people down at intersections makes the roads safer for everyone: drivers, pedestrians, bicyclists, and people using mobility devices. This is only one option: There are many more other solutions to make our roads safer for everyone.

Unfortunately, the language we use obscures these choices, because crashes are framed as freak events, instead of a systemic problem that has solutions that we can choose to implement with the ways we invest our transportation dollars. Referring to collisions between road users as “crashes” instead of accidents is a small, but vitally important shift that helps people change how they think about how to improve our roadways, and starts to move us away from the idea that non-drivers are the cause of crashes.

Why are we talking about this now? Well, there’s a lovely little bill wending its way through the Vermont State House which helps to address these changes in how we think and talk about crashes. It’s long and seemingly about minutiae around vehicular laws (including boats). But there’s a hidden gem in this bill that we want to highlight.

It’s on page 34 and calls for changing the word of “accident” to “crash” throughout Title 23, the Motor Vehicle part of statute. We’re excited about this, because it’s a small, but significant, step towards helping people understand the real changes we need to make in order to keep everyone safe.

Road design obviously needs to change to serve all Vermonters. Hopefully an incoming infusion of infrastructure dollars, along with creativity on the part of municipalities, VTrans, and legislators, will make this possible! In the meantime, though, words matter, and we hope that this statutory change is just the first step in improved communication. Because in order for change to happen, we need to realize that crashes truly are no accident. They are a result of decisions we’ve made about how we design and structure our roadways.

When we change our language, we change our thinking, and when we change our thinking, we change our choices. Those choices will move us toward a safer, more accessible transportation system for everyone.

Mary Catherine Graziano has a decade and a half of experience in education, program coordination, and community outreach, with emphasis on systems development, public outreach, and trainer training. In her role as Senior Manager of Education and Safety for Local Motion, she manages multiple projects related to outreach and training, with a focus on bicycle and pedestrian safety, skills, education and community engagement. Her work to support schools, communities, and local organizations in promoting walking and biking have given Local Motion’s many partners the resources they need to make active transportation and recreation safe and enjoyable for all Vermonters.

Cover photo by Bob LoCicero taken in Richmond, Vermont.