By Faith Ingulsrud

Three years ago, I gave up my beloved rural home and moved to the big city. Weary of depending on my car and mindful of the environment I’d need for healthy aging, I jumped at the chance to live in Burlington’s South End. I feel so lucky now, to be in a place where I can stride out to catch the bus in the morning and zip around on a bike for errands, free from my metal exoskeleton!

The opportunity to opt out of driving is a rare and precious thing, and something increasingly in demand by young and old alike. Vermont has a wealth of walkable settlements but in areas with plenty of jobs, like Chittenden County and the Upper Valley, the number of available homes lags far behind the demand. Even the less economically vibrant parts of the state need more housing options, especially for people who are down-sizing and seeking accessible, affordable and energy efficient homes.

Housing shortages make buying or renting a home frightfully expensive. Renting a 2-bedroom home in Chittenden County for example, costs an average of $1,300 a month. With a 1.8% vacancy rate (3-5% is optimal), rentals are not only hard to find but require a salary that pays $30/hour. Rents are lower in other parts of the state, but wages are correspondingly lower, putting homes out of reach for Vermonters statewide.

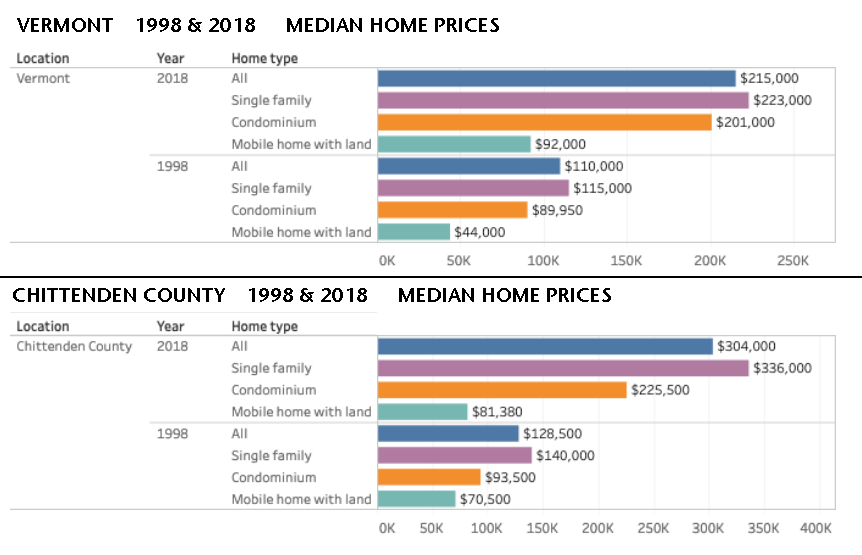

The average cost of buying a home may not appear alarming, but what these numbers fail to show is the poor condition of many of the lower cost homes. I learned this first hand in my multi-year search for a home in Burlington. When you factor in the cost of renovating a dilapidated house at or below the median price, the cost to bring it up to a decent quality can easily rise to $500,000. When people can’t find a house they can afford they end up commuting long distances.

If they can’t live close to work, school and services, people drive more. Data show that in Vermont, those who live in walkable places log significantly fewer vehicles miles than people who live in suburban and exurban places.

Attracting more residents into existing neighborhoods also makes good fiscal sense. It takes advantage of significant public investments that already exist in our cities and larger villages. Water, sewage treatment, streets, sidewalks, parks, transit and school facilities all support the concentration of people and buildings that can attract jobs, services and amenities.

Sidewalks, bike infrastructure, buses, and the public facilities that improve the quality of life, are expensive to install and maintain over time. The costs–borne by taxpayers and property owners–become more manageable when infill development adds new residents to help share the burden.

Barriers to homes in walkable places

With a strong market demand and clear public benefits, why aren’t we seeing more construction of homes in our walkable villages? Here are three reasons the supply is lagging far behind demand:

- Not enough developable land. In existing cities and neighborhoods – the limited supply of buildable land and redevelopment opportunities is a given. Where developable land exists, there may be other factors that either preclude development or drive up the costs to a level that makes it too risky. These include the presence of wetlands or steep slopes, contaminated soils, insufficient water supply, and the lack of sewer capacity.

- High cost of construction. Anyone who has completed a home building or renovation project recently knows how much construction materials and labor cost. Add to that the shortage of contractors and laborers and you can get a sense of why new homes cost so much.

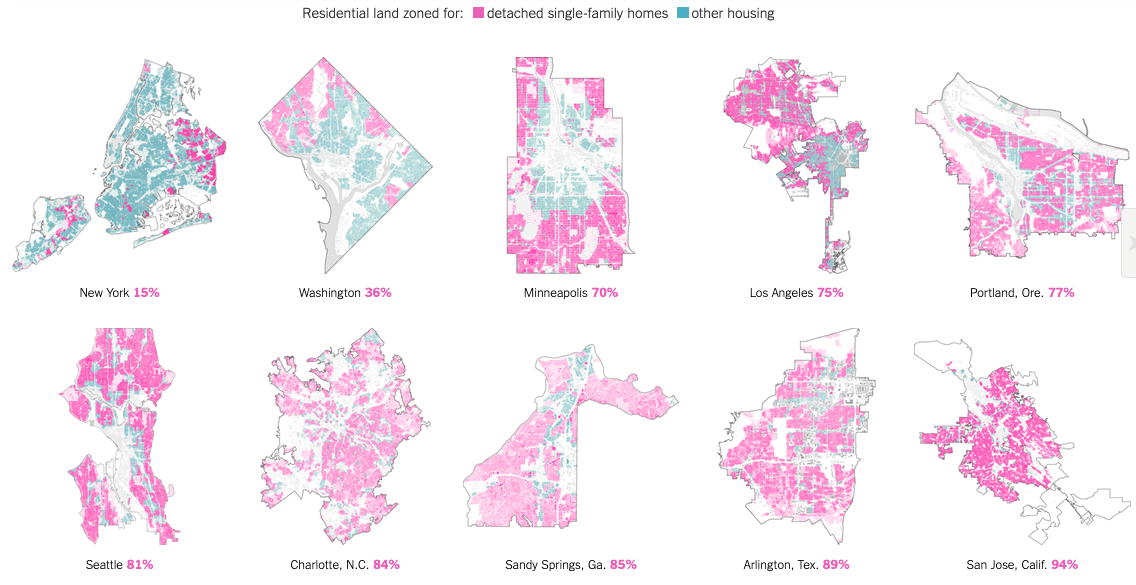

- Outdated Zoning/Land Use Regulations. The 1960’s and ‘70’s-era zoning and subdivision regulations adopted widely by Vermont municipalities elevate single-family detached homes above all other types of homes, while mandating large lots and ample parking. This severely limits the opportunities for new homes in neighborhoods that recieve public services.

At the state and local levels, there’s not much we can do about the high cost of construction, but we can change regulations to better support redevelopment in walkable places. Development within cities and villages is more complex and expensive than green field projects, so for infill projects to pencil-out, governments must restructure regulations to protect public interests without needlessly adding time and cost to redevelopment projects.

At the Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) we are working with other agencies to modify state permitting programs for this purpose but we also see the need for municipalities to update zoning and other rules governing development. In many towns, the existing zoning requirements are out of sync with the historic pattern of buildings, lots, homes and mixed uses. Even without a housing shortage, it makes sense to enable and reinforce the historic settlement pattern. This has the added benefit of supporting walkability while honoring the traditional neighborhoods we know and love.

Zoning updates could also enable the construction of Missing Middle homes that fit well with the character of existing neighborhoods, and provide people with smaller, more modestly priced units. Missing middle housing such as duplexes, cottages and townhouses meet the needs of a growing number of small households.

In Vermont, downsizers are competing for the same homes in walkable places as young adults, raising costs at both ends of the age spectrum. With Vermont’s demographics tilting precariously towards older people, balance is only possible if we can offer young adults the conditions they need to succeed in life. That starts with making sure there are homes they can afford, and in places where car ownership is optional. More missing middle homes in our existing neighborhoods can provide places where both young and older adults can live without a car, as many now prefer.

We have met the enemy, and it is us

What’s keeping us from building the housing we badly need? At the top of the list is an entrenched bias in favor of the detached single-family home coupled with a strong aversion to change. Federal policies and a history of bad development have helped shape these attitudes.

Tax policies like the federal mortgage interest deduction, encourage us to invest heavily in the purchase of a home. With our life’s savings at stake, we become hypersensitive to any change that might affect the value of that investment. As a result, infill development projects represent uncertainty and are often perceived by neighbors as a threat.

Further intensifying our protective reactions are bad development experiences from the past. This is especially true for baby boomers who came of age during the great suburban buildout of the 20th Century–a time when we abandoned the practice of building walkable towns in favor of auto-dependant sprawl that over time, became the norm.

Too many of us saw growth that destroyed the places we loved. Development became synonymous with degraded environments and sprawl. Consequently, when we find a home and neighborhood we like, it becomes a haven that we are determined to protect from any change.

But we’ve learned a lot in the past 20 years about how to do development right. We’ve rediscovered the fundamental value of walkable places. It takes time and often a generational shift for institutionalized plans, practices, policies and attitudes to shift to a new paradigm but our state and municipalities are slowly undoing the damage of past policies and learning how to support better development, including an emphasis on redevelopment of existing settlements and re-investment in our existing public facilities.

Attitude adjustment

In the meantime, we have a crisis. People want homes in walkable places but can’t find them and are forced to live in places where driving is the only transportation option.

We can all help relieve the situation by re-examining our attitudes about change. Here are some typical assumptions I hear in everyday conversations about redevelopment:

- Development means more traffic

- More residents in my neighborhood will make my life worse and burden our community

- More space is better (large lots, houses, and setbacks)

- Rental housing will lower the character and value of my neighborhood

- Developers exploit communities to make money

- Onerous permitting processes and local opposition keeps communities strong by repelling developers

- Resisting change is a virtue

Sound familiar? We could identify the grains of truth and dispel the falsehoods for each of these, but for now, let’s focus on traffic.

Increased traffic is often cited in opposing development of new homes. This concern makes sense in auto-dependent settings where every trip to and from a new home is likely to be in a vehicle. In walkable places, the anti-congestion argument works against the goal of expanding transportation options to more people. Since living in a walkable location is the most effective way to cut down on driving, the overall transportation system will benefit from the increased number of people who can walk, bike and use transit. Yes, the new homes will generate traffic, but those trips will likely be shorter and less frequent than trips made from a remote location.

What’s also lost in the haze of traffic fear are the benefits of having more neighbors–additional taxpayers who will share the cost of maintaining sewer and water systems, streets, sidewalks and parks. New homes will add more bus riders to support fledgling transit systems, and aggregates potential customers to justify the installation of high speed internet. If we plan, design and retrofit neighborhoods right, those new residents will find walking, biking or transit a better choice than driving.

What you can do

A single family neighborhood in a walkable location can preserve its neighborhood character by allowing some gentle density increases for more homes. Having an additional unit may even help existing residents manage personal, family and financial changes at various life stages. Consider the fact that densities naturally rise and fall in stable neighborhoods, and with the smaller households we have today, the density of people living in your neighborhood today is likely to be much smaller than it was in previous generations when households were larger.

If you live in a walkable neighborhood, think about what really makes your neighborhood great. Single-family homes and low densities are not an essential ingredient. Think about what other elements that give you neighborhood value, and the simple ways you can increase neighborliness to enhance your life and preserve neighborhood character.

Consider sharing your walkable neighborhood with a few more households, and work with your town to support changes to the zoning and other land use regulations that will make it possible.. Here are some of the ways that communities across the country are tackling the zoning challenge.

I’m thrilled to be part of a stellar team, gearing up to produce Vermont-specific guidance for housing-ready regulations. The upcoming guide produced by DHCD and its partners will offer practical tools for weeding out the bias toward cars embedded in your local regulations, and creating zoning that encourages an appropriate mix of housing in your walkable town centers.

Healthy neighborhoods are resilient ecosystems that can handle modest changes. Your positive attitude toward infill can be contagious and make all the difference when housing-ready zoning changes are proposed.

We don’t need expensive transportation investments to lower our carbon footprint. We can reduce the need to drive by removing unnecessary barriers to neighborhood redevelopment. Let’s make room for the Vermonters who want to live in walkable neighborhoods, making our travel more sustainable, communities stronger, and improving our health and the environment.

At the time of writing, Faith Ingulsrud managed the Zoning for Great Neighborhoods project at the Vermont Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD), where she worked with the Community Planning + Revitalization group. This entry originally appeared here.

Header photo by Julie Campoli