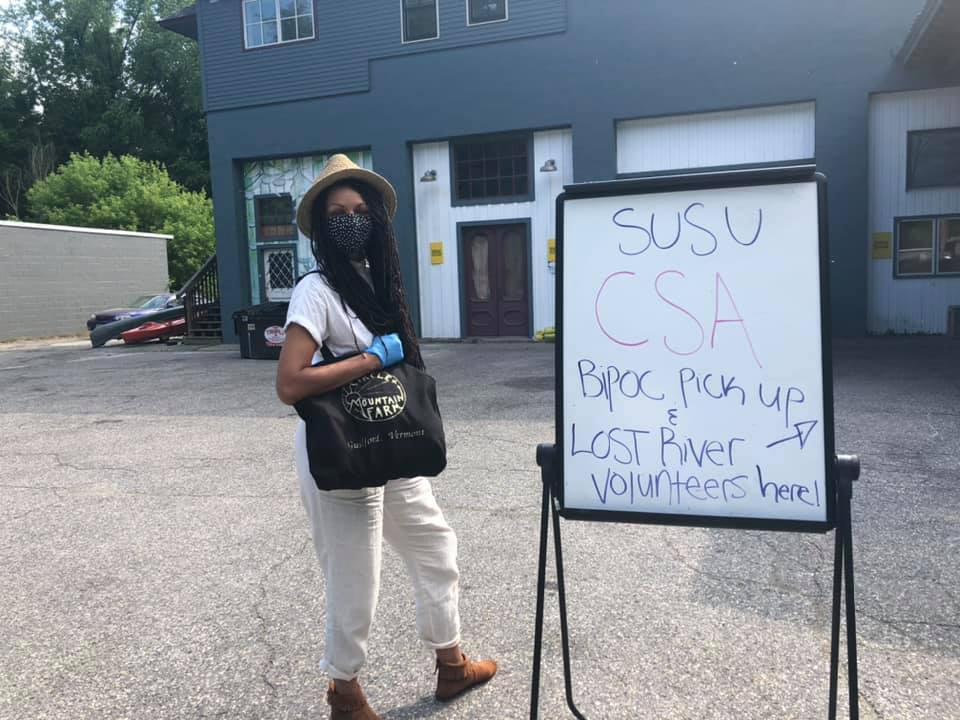

Amber Arnold and Naomi Doe Moody lead the SUSU Healing Collective in Brattleboro, Vermont. Learn more about the BIPOC Land and Food Sovereignty Fund at gofundme.com/f/bipoc-healing-foods-fund.

Lydia Clemmons, PhD, MPH, is President of Clemmons Family Farm, Inc. in Charlotte, Vermont, a 501c3 nonprofit organization (where Arnold also serves as a K-12 curriculum content developer). Learn more at www.clemmonsfamilyfarm.org.

This article also appears in the Summer 2020 issue of the Vermont Environmental Report. Read it here.

When COVID-19 arrived in Vermont, food access and availability emerged front and center. A University of Vermont survey found that food insecurity in the state rose 33% during the early stages of the pandemic. Meanwhile, it became clear that Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) were bearing the brunt of the virus in Vermont as they were nationwide, due to compounded disparities in health, housing, and employment that stem from systemic racism.

In May, the BIPOC-led SUSU Healing Collective in Brattleboro, which offers instruction in spiritual and plant-based healing, thought about ways to help its community. Amber Arnold, Naomi Doe Moody, and Lysa Mosca watched as food flew off the shelves in grocery stores and food pantries. They knew that much of the food relief being handed out at various sites around the state was processed or non-perishable. They thought about how during a pandemic, healthful food was more important than ever, especially for vulnerable populations.

That’s when SUSU got the idea to purchase Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm shares for people of color in their area. In just one week, with donations from a GoFundMe campaign, they provided 23 families in Brattleboro with fresh food from local farms. It wasn’t easy, as the group struggled to find farms that had not yet sold out of their CSA inventories. But after they managed to secure full shares from two nearby farms (one in Vermont, the other in Western Massachusetts), other local businesses chipped in what they could: meat, herbs, flowers, gift cards, and more.

“On top of all the trauma of dealing with being a Black person in America, you shouldn’t also have to worry about finding food to take care of your body,” says Arnold. While for many white Americans, the murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer in Minneapolis struck a fresh chord around reckoning with racism in this country, Arnold says that for Black people, “George Floyd, police brutality, and systemic racism are a normal part of our everyday experience. With the CSAs, we wanted to send the message to our communities that they deserve to be nourished; they deserve to be healed.”

It didn’t end there. “There are only so many shares you can actually purchase. People were looking to change a system,” says Moody. So the team at SUSU launched the BIPOC Land and Food Sovereignty Fund, invoking the idea that all people should have the right and means to define their own food and agriculture system. SUSU’s vision is to purchase farmland in southern Vermont where farmers of color can learn about and honor their ancestors’ sustainable growing practices, and begin healing from a painful history of land-based oppression. SUSU names Soul Fire Farm in Grafton, NY as a model for what it hopes to accomplish, as well as a 2019 book called Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement.

As of this writing, the SUSU Healing Collective has raised nearly $119,000 of its $400,000 goal. When it manages to purchase farmland, it will be an anomaly. Census data from 2017 tells us that just 36 of a total 6,808 farms in Vermont are either owned or co-owned by Black people, and only 17 are owned by Black people alone. According to data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), of the 1.2 million acres of farmland in Vermont, only 3,960 acres (0.33%) are Black-owned or principally operated.

Some of this data was relayed to VNRC by Lydia Clemmons, President of Clemmons Family Farm, Inc. in Charlotte, Vermont, whose mission includes conserving and stewarding the physical 148-acre farm, which is one of just 0.4% of Black-owned farms in the nation. After more than 50 years growing organic hay, alfalfa, and a variety of organic food crops, the Clemmonses recently established a hoop house that produces organic vegetables that are part of African-American and African culinary heritage, with plans to foster food sovereignty from this perspective.

The culinary heritage program is implemented in part through “And Still I Rise,” a new collaboration with Krista Scruggs of Zafa Wines, who planted a new 75-tree apple orchard on the Clemmons farm this Spring and who also recently purchased her own farm in Isle la Motte, Vermont.

Clemmons Family Farm also operates a cultural center on the physical farm to celebrate the arts and heritage of the African diaspora. The farm is one of the 22 official landmark sites on the State of Vermont’s African-American Heritage Trail.

“Nationwide, African Americans have lost 93% of their land assets since the time that my parents were infants,” Clemmons told VNRC, referring to the elder Lydia and Jack Clemmons, who bought the property in 1962 and are now both 97 years old. In June, the Clemmons family was featured in an educational video produced by the Office of Senator Bernie Sanders about the low number of Black farmers in the United States, and the dearth of equity that persists as a result.

“A people with no land is a people with no future, no leverage point, no equity,” says Clemmons (daughter) in the film. She told VNRC that an important part of furthering racial equity in a majority-white state is creating social capital for Black farmers and farmers of color, and BIPOC leaders of all types of organizations in Vermont, and helping them to own and steward their own land.

Clemmons’ parents farmed their land and refurbished their six historic buildings while pursuing medical careers at the University of Vermont. They enjoyed strong, longstanding ties to their community, and Clemmons and her four siblings all received higher education whose costs were covered in part by the farm’s commercial hay crop (Clemmons herself holds a PhD in medical anthropology and a Master of Public Health). Still, Clemmons recalls watching white peer organizations in Vermont build their farms and futures with greater ease, receiving substantial agriculture grants simply because they knew the right people at the right organizations who were offering help and keeping them in the loop when the requests for grant applications were open.

“White farmers and landowners somehow were accessing these agriculture grants easily, but when we inquired, we felt we were being run in circles. It took me finally making a recent phone call to the Black Family Land Trust in North Carolina to ask for help. When they got on the phone with other organizations in Vermont, the agriculture grant opportunities, technical assistance, and technical information that had evaded us for years suddenly opened up to us. We are now starting to receive the kind of support we’d been watching white farmers and landowners receive for years,” says Clemmons.

Outright discrimination, of the kind where the USDA routinely denies loans or grants to Black farmers, has been well documented. But Clemmons is equally concerned with favoritism, its less visible, and perhaps more insidious companion. It’s basic human behavior: We tend to help people we know, people who are known to our friends or colleagues, or people who look like us. In a predominantly white conservation system, operating in a predominantly white state, it follows that white-led institutions would be more likely to share information and support through established networks of white farmers and conservationists, and in doing so — intentionally or unintentionally — deprive people of color, who are not in the same networks, of those same opportunities.

“Equity does not mean ‘equal,’” says Clemmons. “It means we need to seek out and invest more in BIPOC-led organizations, to bring their capacity to a level where they can do the work they want to do.” Clemmons says organizations hoping to support diverse groups of Vermonters should not assume that everyone is accessing the information and opportunities they offer, even if they are publicly available. “Many of the people seeing your website know to look there because people have told them about you, or have already connected them with other resources that brought them there,” she notes. “Do not assume that BIPOC-led groups or individuals have that same connectivity.”

Arnold of the SUSU Healing Collective says that grants from white-led institutions are often well-intentioned, but the guidelines they impose can be limiting. What Black and Brownled organizations need most is to be trusted to create the spaces that they need, “which only we know how to do,” she explains. Similarly, Clemmons recommends that white-led organizations give resources directly to BIPOC-led organizations to determine their own endeavors, and then step back as advisers.

The Clemmons Family Farm began its story in Chittenden county nearly 60 years ago, and the SUSU Healing Collective’s dreams of a BIPOC-centered farm in southern Vermont is still in the works. But Clemmons and Arnold, two generations of African-American Vermonters, are optimistic. “If we are able to have this platform, it lets the generations coming after us know that if we can do it, so can they. We want to create a little space so the generations after us can create bigger things, just like our ancestors did for us,” says Arnold.

One comment on “Growing Food Sovereignty, Equity, and Social Capital”

Comments are closed.